Programme de la SEECHAC

Programme des conférences ouvertes aux membres de la SEECHAC pour le premier semestre 2009 :

-

- Le jeudi 29 janvier 2009 :

« Les méditations de la Reine Vaidehî » par Jacques Gies,

Président du Musée National des Arts Asiatiques Guimet. - Le jeudi 26 février 2009 :

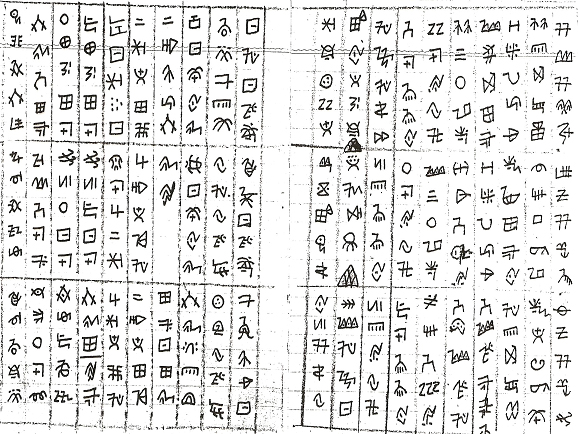

« Le chamanisme à écriture Yi, un enjeu politique en Chine »

par Aurélie Névot, Chargée de recherches au CNRS.

- Le jeudi 29 janvier 2009 :

À la différence

des autres pratiques chamaniques répandues dans le monde, les chamanes

yi, appelés bimo ou « maîtres de la psalmodie », opèrent par

le moyen de manuscrits. Bien que les livres soient au fondement des

représentations du monde de leur société « à moitiés » – établie

au Yunnan (Chine) –, il ne s’agit pas ici d’une « religion du

Livre » au sens où l’on emploie ordinairement cette expression, mais

d’une religion de l’écrit. L’écriture en présence, différente

de l’écriture chinoise, a la particularité d’être exclusivement

rituelle, secrète et réservée aux seuls initiés bimo. Nullement

dogmatique, elle assure la communication entre le monde des humains

et celui des esprits. En quoi consiste cette écriture chamanique et

comment s’est-elle transmise au cours des siècles ? Qu’entend-on

par « chamanisme à écriture » ? On proposera de répondre à ces questions

en tenant compte des changements sociaux qui affectent la population

yi : on s’interrogera en particulier sur la dynamique contemporaine

mettant en relation la religion et l’écriture avec le pouvoir dominant.

Car soucieux de maintenir sa tutelle sur les pouvoirs locaux, l’État

chinois s’engage dans un processus d’uniformisation et de laïcisation

des rituels et de l’écriture chamanique qui bouleverse les fondements

politico-religieux de l’ethnie.

Ouvrage

Comme le

sel, je suis le cours de l’eau. Le chamanisme

à écriture des Yi du Yunnan (Chine), Nanterre, Société d’ethnologie,

2008

- Le jeudi 26 mars 2009 :

« A comparison between Nepalese and Bengal sculpture, Pala period »

par Adalbert Gail, Professeur à l’Université Libre de Berlin.Bengal and Nepal stone sculpture

– a comparison from a religous point of viewA comparison of Bengal and

Nepal stone sculpture exhibits close affinities as well as distinct

differences.The Uma-Mahesvara murti is

the most ubiquitous Saiva icon in both areas, while the Ardhanarisvaramurti,

on the other hand, is the rarest one. The high respect towards the individuality

and independence of Devi, the Great Mother, might be an adequate explanation

for that phenomenon.Regarding Vaisnava sculpture

a tripartite group is predominant in both countries: while, however,

Bengal favours a central, four-armed Visnu flanked by Laksmi on his

right and Sarasvati on his left side, Newar art prefers central Visnu

accompanied by Laksmi on his right, yet Garuda on his left side. Here,

the exchange of Garuda by Sarasvati in Bengal can well be interpreted

as a purposeful humiliation of Brahma, who preserved just a marginal

competence as priest and gardien of the zenith. Brahma’s aspect as a

god of creation, in many other Indian areas expressed in the form of

the so called trimurti, is absent both in Bengal and in Nepal;An important specimen in respect

of Hindu sculpture is the image of Surya.In Bengal there is much evidence

of the existence of a particular sect of sun worshippers attested by

a large amount of elaborated images. The adherents of that sect, the

Sauras, called themselves Paramadityas according to inscriptions. Surya

wears boots and – in contrast to Western India – no armour (kancuka),

but an upper garment as many other Indian gods. Surya’s entourage consists

of the traditional acolytes Dandin and Pingala, two wives and two arrow-shooters.

While Surya enjoys hight respect by Hindus as well as by Buddhists in

Nepal a particular Saura sect cannot be proved, as I have pointed out

in a recent article on Sun Worship in Nepal(Pandanus 01, 2008).

The fate of Buddhism

is quite different in both areas. In Bengal Buddhism came to an end

with the Pala and Sena dynasties in 13th century, in Nepal Newar Buddhism

is still alive, yet much assimilated to Hindu ritual and imagery.The early Pala period in Bengal

(750-900 AD) corresponds to the late Licchavi period in the Kathmandu

valley. The figure of the Buddha is more or less similar in both countries,

both continue the Sarnath tradition of the smooth and the Gandhara tradition

of the pleated garment (samghati). Among the Bodhisattvas Avalokitesvara

seems to be the most popular one. In Bengal the most prevalent type

of image is a stela consisting of a flat backside and figures in more

or less high relief. The Hindu stone sculptures have varied forms. The

most prevalent Buddhist stone sculptures in Nepal are

caityas exhibiting the Buddha, the metaphysical Tathagatas,

Bodhisattvas and other divinities.A unique type of image in Nepal

is an octagonal (around 1 m high) stone, the Dharmadhatuvagisvaramandala.

Its upper surface is a round disc covered with figural or symbolical

representations of Buddhist deities. The main figure, however, is Manjusri

or Vagisvara, the mythical creator of the Kathmandu valley.Concluding our short survey

we come back to the beginning: among many masks of Avalokitesvara his

appearance as Halahala-Lokesvara with his Prajna is a magnificent Buddhist

adaptation of the popular Uma-Mahesvara icon in Nepal. - Le jeudi 28 mai 2009 :

« Images chinoises anciennes du Vimalakîrtinirdesa »

par Christine Kontler Barbier, Chargée d’enseignement à l’Université

de Tours et à l’Institut Catholique de Paris.