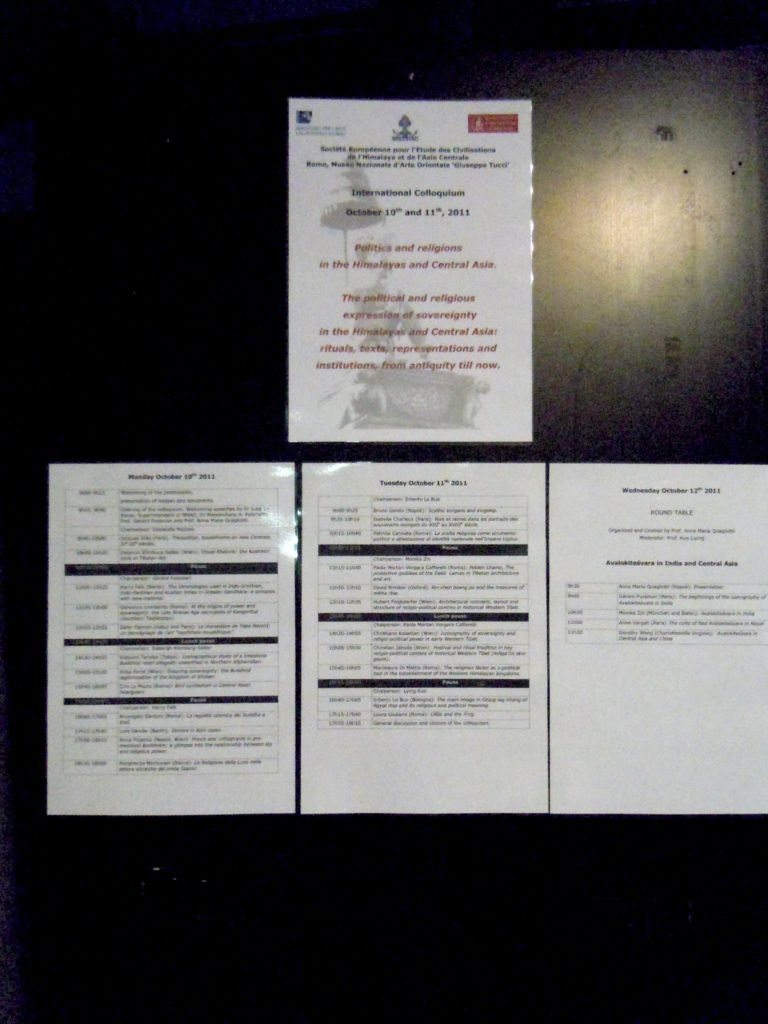

« Politics and religions in the Himalayas and Central Asia »

“The political and religious expression of sovereignty

in the Himalayas and Central Asia:

rituals, texts, representations and institutions,

from antiquity till now”

Rome, Museo Nazionale d’Arte Orientale ‘Giuseppe Tucci’, 10th and 11th of October 2011

Harry Falk (Berlin)

The chronologies used in Indo-Scythian, Indo-Parthian and Kushan times in Greater Gandhara: a synopsis with new material.

In the last ten years I proposed interpretations of new and well-known data on the diverse chronologies in a number of publications, viz. Yavana cum Azes (2009 with Chris Bennett), Maues (2011), and Kushan (2001, 2004,2009). The present synopsis aims at summarizing all systems in a form which demonstrates how to understand their origins and interlinkages. A new reliquary dated in the early times of Azes will be presented which seems to strengthen the proposal made before that the year Azes 1 is not necessarily the first year of his accession.

Giovanna Lombardo (Roma)

At the Origins of Power: evidence of rituals and of beginning of social diversification in the composition of grave furniture appearing in the Late Bronze Age necropolis of Kangurttut , Southern Tajikistan (middle of II millennium B.C.).

The aim of this paper is to consider the grave furniture of the necropolis of Kangurttut, in the upper Vakhsh valley, in Southern Tajikistan, analysing its composition with special regard to the various types of pottery vessels, and to the other objects appearing in the graves, also in comparison with other necropolises.

I shall try in this way an interpretation of funerary rituals, especially in connection with the use of the cenotaph burial, which is frequent in Southern Tajikistan in the middle of the II millennium B.C., and is the prevailing burial form in the necropolis of Kangurttut.

Through the analysis of the grave furniture I shall also try to put in evidence the existence of a rising social stratification in an important site belonging to the farming Sapalli culture of Bronze Age Northern Bactria (Southern Tajikistan and Uzbekistan).

Zafar Paiman (Kabul-Paris)

Le monastère de Tepe Narenj : un témoignage de l’art « hephtalo-bouddhique ».

Les fouilles du monastère bouddhique de Tepe Narenj, situé sur les hauteurs de Kaboul, ont été entamées en 2004, sous notre direction, par une équipe afghane. Elles ont permis la mise au jour progressive de divers monuments, remarquables à plus d’un titre, étagés à flanc de montagne, notamment un grand stupa, un groupe de cinq chapelles, ainsi que les restes de statues colossales, en argile comme toutes celles découvertes jusqu’à présent sur le site. L’ensemble témoigne, par son ampleur et la qualité d’exécution des sculptures, de l’importance du monastère.

A l’intérieur de l’une des chapelles figuraient, parmi les dévots sculptés de part et d’autre d’un buddha assis monumental, un roi agenouillé et des laïques debout chaussés de bottes, tandis que, dans la partie basse du monastère, un couple princier en prière, un Buddha et un grand bodhisattva ont été découverts côte à côte.

Les résultats des fouilles permettent, pour le moment, de situer la durée d’activité du monastère entre le milieu du 5è et la fin du 9è siècle, c’est-Ã -dire sous le règne des Hephtalites puis des Hindu Shahi, dont des monnaies ont été mises au jour.

Il semble que la partie haute de l’ensemble n’était accessible qu’à un nombre réduit de fidèles, appartenant sans doute à la noblesse, contrairement à la partie basse, plus largement ouverte aux pèlerins.

Le site témoigne, ainsi que d’autres établissements de la région de Kaboul, de la protection accordée aux communautés monastiques par les Hephtalites, ainsi que de la continuité du bouddhisme dans la vallée, sous le règne des souverains hindu shahi.

Katsumi Tanabe (Tokyo)

Iconographical Study in a limestone Buddhist relief allegedly unearthed in northern Afghanistan–The two Buddhas juxtaposed under the Bodhi-Tree–

The aim of this paper is to clarify the iconographical meaning of a quite unique relief made of whitish limestone which depicts an unprecedented scene of the two Buddhas staying side by side with each other on the same wide seat and under the Bodhi-Tree. The fact that the material of this piece is whitish limestone suggests beyond any doubt its provenance as northern Afghanistan or southern Uzbekistan. This limestone relief might be dated either to the late Kushan period or from the third to the fourth century AD.

One of the two Buddhas is sitting in paryaṅkāsana while the other is standing (sthānaka). The seated one is identified as the Buddha Śākyamuni who has already attained the perfect Enlightenment. However, it has passed one week or so since he has got perfectly enlightened, because he does not take the dhyāni-mudrā anymore but is attaching his right forefinger to the right cheek as if he is wondering or meditating. Furthermore he is looking at the Bodhi-Tree. The other standing who is also gazing at the Bodhi Tree is Śākyamuni as well, not one of the Past seven Buddhas nor of future Buddhas.

They share the same seat, in other words, each Buddha occupies half of the seat. The juxtaposition of the two Buddhas sitting on the same seat is called in Buddhist literature as taking ardhāsana (half seat). However, the two Buddhas depicted on the relevant relief have nothing to do with the so-called ardhāsana, despite the fact that they seem to divide one seat into two parts and each takes only its half. The reason why the two Buddhas are juxtaposed on this relief can be explained by the episodes of Śakyamuni after his Enlightenment at Uruvela. According to the descriptions of the Mahāvastu and the Lalitavistara, the Buddha Śākyamuni continues to gaze at the Bodhi-Tree sitting in paryaṅkāsana (crossed-legs) posture for seven days, and after these days he stands up from that seat (siṅhāsana) and again continues to gaze at the Bodhi-Tree. Therefore this relief combines these two different acts (sitting and standing) of the Buddha Śākyamuni and depicts them at the same time and in the same relief just as the Early Indian Schools did at Bharhut, Sānchī and so on.

As for the date of this relief might be decided by the ribbon-diadem wound around the trunk of the Bodhi-Tree. It is related to Sasanian ribbon-diadem often wound around the shaft of sacred fire-altar as is depicted on the reverse of Sasanian coins issued from the reign of Hormuzd I (272/73) to that of Kawad I (484-531). In this regard, the Kushano-Sasanians or their art might have been involved in the transmission of this royal motif to the Buddhist art of northern Afghanistan and southern Uzbekistan. In addition to this, a dated relief unearthed from Kāpisī region of eastern Afghanistan supplies us with a narrower date around 300 AD, because it depicts also the Bodhi-Tree with a ribbon-diadem similar to the one depicted on our relief.

Erika Forte (Wien)

Ensuring sovereignty: the Buddhist legitimation of the Kingdom of Khotan.

The close tie between political sovereignty and religious (specifically Buddhist) power is a dominant characteristic in the cultural history of the kingdom of Khotan during the 1st millennium CE. The legendary accounts of the founding of Khotan in all their variants consistently connect the origin of the kingdom to some Buddhist epiphanic events. The paper will analyse how this connection is expressed in the artistic production of the Khotan oasis.

Arcangela Santoro (Roma)

The universal sovereignty of the Buddha at Kizil.

Often on the barrel-vaulted ceilings of the Kizil grottoes a median strip appears along the zenith line, featuring complex pictorial decoration.

Along this band – indicated by a simple coloured background, sometimes with border lines – appear, one after the other, portrayals of the sun and moon, naga and garuda figures, deities of the winds and standing Buddha figures, surrounded by tongues of flame. These are often accompanied by groups of flying geese, arranged like a Catharine-wheel around the heavenly bodies (sun and moon).

In my opinion, this composition, also considered in a recent article (Tianshu Zhu, The Sun God and the Wind Deity at Kizil, Eran ud Aneran, Venezia 2006, pp. 681-718,), showing the heavens or heavenly kingdom, portrays the universal sovereignty of the Buddha.

Lore Sander (Berlin)

Donors in the Kizil Caves.

Since Heinrich Lüders published his epoch-making articles on the donation formulas in the 1922 and 1930 the connection between Kizil and the Tokharian royal court in Kucha is well known. The time of increasing importance of this place points back to Kanishka times (2nd century A.D.), and lost it after the occupation of Kucha by the Tang armee in 648. The aim of my paper is to show the connection between the royal court and Kizil from different points of view, the historical, the literary and inscriptional, but also how they represented themselves in the wall paintings.

Margherita Mantovani (Roma)

The Religion of Light in the Hebrew Letters of Prester John.

The aim of this work is to analyze the figure of Prester John as a king rather than as a Christian Patriarch, and, in particular, the symbolism of the palaces of light compared with the three palaces and the three realms in the Chinese Manichaean catechism. The Hebrew version of the false letters (published in 1982) is involved to modify the traditions of the Acts of Thomas in a Manichean sense. It is confirmed J. Pirenne’s thesis that the Hebrew version – contrary to the established tradition until the eighties of the last century – is the original text of the false letters of Prester John, written by a Jew author, probably from Provence. An author who demonstrated to know the conflict between the dynasty of the Manichean Carachitai and that of Islamic Seljuks at the beginning of the XII century.

Isabelle Charleux (Paris)

Couples trônant et souverains Chakravartin: rois et reines dans les portraits de souverains mongols du XIIIe au XVIIIe siècle.

Les représentations de souverains en Mongolie se divisent en deux catégories principales : les représentations du pouvoir où le roi, accompagné de sa reine située sur un pied d’égalité, est entouré de paladins et d’attributs du pouvoir, et les icônes représentant le souverain seul divinisé, dans une frontalité rigide. En tentant de comprendre les différentes fonctions de ces portraits – publique ou privée, politique, religieuse ou funéraire –, je tenterai de montrer comment les portrait iconiques du souverain divinisé, issus du bouddhisme et/ou du culte des ancêtres, ont progressivement remplacé les portraits politiques.

Patrizia Cannata (Roma)

Religions as a tool for political control and national identity’s statement:

the case of the Uyghur Empire.

Among the nomads of Inner Asia, before the spread of Islam, we rarely find at any time a “state religion”, rather we find a choice of beliefs that come up by the side of shamanic cults and ceremonies: Uiγur qa’ans in VIII-IX centuries were the only exception.

Paola Mortari Vergara caffarelli (Roma)

Pelden Lhamo, the Protective Goddess of the Dalai Lamas, in the Tibetan architecture and art.

Pelden Lhamo, “the Glorious Goddess” (Shri Devi), is considered as the Great Protective Deity of the Dalai Lamas. Since 15th to 20th century the highest religious and political authorities of Tibet dedicated to the goddess several sacred buildings and figurative representations. The best example of the privileged connection of Pelden Lhamo with the political life and the religion of the country is the monastery of Chokorgyel. It was founded by the second Dalai Lama (1475-1542) in the vicinity of the Lhamo Latso, the Oracle Lake where the spirit of the goddess is said to reside.

Hubert Feiglstorfer (Wien)

Architectural concepts, layout and structure of religio-political centres in Historical Western Tibet.

The structural and territorial organisation of the early Tibetan polity (7th-9th centuries) demonstrates a significant overlapping with old clan territories which corresponds to the relationship between state authority as represented and embodied by the sacred kings (btsan po) and powerful aristocratic clans, some of whom managed to preserve their influence over areas under their control from pre-imperial times. Characteristic elements of this form of political organisation, such as the holding of courtly assemblies, can also be found in the early phase of the West Tibetan kingdom and indicate a certain continuity of concepts inherited from or projected backward onto imperial times and traditions. They correspond to a political geography with a mobile centre prevalent in the imperial era which was later followed and replaced in Central Tibet by new concepts of religio-political centres – such as the “lHa-sa Maṇá¸?ala Zone”. 1

Research on the guiding concepts and principles which governed the establishment of religio-political centres in the West Tibetan kingdom (Tholing being an example of one such early key site) is for a number of reasons still in its infancy. In many respects the original layout and structure of these sites as well as their further development have still to be identified and are as yet only little understood.

Based on extensive field research, this paper will investigate spatial and architectural aspects of selected religio-political centres, with a focus on sites distinguished by early royal foundations of important Buddhist monasteries, such as Tho ling in Guge, ‘Khor chags in Pu rang and Nyar ma in Ladakh. Additional comparative data relate to Tabo in Spiti valley, Alchi in Ladakh as well as the recently discovered Buddhist sites in mKhar rtse valley, the later based on documentation carried out by Tsering Gyalpo.

An important question concerns the location and orientation of temples and palaces, their position and relationship towards one another as well as their relation to natural phenomena such as mountains or rivers and underlying cosmological or mythological concepts. Another issue that will be discussed in particular with regard to the layout of early Buddhist complexes is the question of a fundamental architectural system of spatial proportions and scales identifiable in the case of single buildings and its components, and perhaps even obtaining for a whole complex. As far as possible this will also include a reconstruction of the historical processes of changes and additions to and renovations of these monuments, often described as mandalic structures. High-resolution satellite imagery of these sites constitutes an important methodological tool that provides a fresh and precise perspective for mapping these religio-political centres. This is complemented by comparative studies of the system of circumambulation paths (skor lam) defined by vertically and horizontally structured religious buildings and a corresponding hierarchy of religious concepts.

The aim of this study is the investigation of religious and political relations in a spatial context which extends from the single structure to a scale involving several political territories.

1 Sørensen, Per K. and Hazod, Guntram (2007) Rulers on the Celestial Plain. Ecclesiastic and Secular Hegemony in Medieval Tibet. A Study of Tshal Gung-thang. 2 Vols. Wien: Austrian Academy of Sciences Press, Vol. I: p. 20, passim; Vol. II: pp. 401ff.

Christiane Kalantari (Wien)

Iconography of Sovereignty and Religio-Political Power in Early Western Tibetan Art.

Images of sovereigns provide and enormous resource for the study of relation between society, power and religion during the time of the West Tibetan kingdom (with the parts Guge, Purang, Ladakh) from the 10th C onwards. The forms and meanings of these images have not yet been studied in their varied aspects: they include religio-political authorities portrayed in assemblies with historical lay and religious figures reflecting strict social hierarchies commemorating historical events; sovereigns are depicted in close relation to local protective deities with great importance for the patrons, and they are depicted in complex narrative scenes engaged in various different ceremonies including banquets and marriage ceremonies. In an attempt to define the broader historic and ideological context I will look at the visual models and the ideas behind these representations. This analysis will also include the ‚symbolic capital’ in this type of imagery such as the depiction of settings, thrones, baldachins and other elements of material and status culture like costumes, as well as markers of military prowess, namely weapons, equestrian culture and emblems. All these elements have hitherto rather been regarded as purely decorative elements and not as representations of emblems of authority, also mentioned in relevant texts.

Previously unpublished material from historically related monuments in mKhartse and Dung dkar (Ngari, TAR/ China) collected during field research in a multi-disciplinary team between 2007 and 2010 allows a comparative study and interpretation of images of the ruling elite within a broader and chronological regional context.

Christian Jahoda (Wien)

Festival and ritual traditions in key religio-political centres of Historical Western Tibet (mNga’ ris skor gsum).

In keeping with the model of political sovereignty established by Srong nge (947–1024), the ruler of the West Tibetan kingdom, all social groups in the societies under his control were subjected to rules and regulations which served to establish and to secure in a permanent way a polity based upon Buddhist principles. After having renounced the throne this was also expressed by him under the name of (royal lama) Ye shes ‘od in a religious edict which contained a kind of constitution of this kingdom giving “priority to religion over secularism”. 1 As a consequence, the representation of religious power also comprised the expression of political power.

An important aspect of religio-political power was related to the cult of protective deities. rDo rje chen mo, a female protective deity (srung ma), seems to have held a particular position as she was installed in this function in the case of several prominent monasteries which were founded during the period of the late 10th-early 11th century by power-holders such as Ye shes ‘od (founder of Tho ling, Nyar ma, Tabo), ‘Khor re (‘Khor chags) and ‘Od lde (Shel).

In all these monasteries and places which at least in the case of Tho ling, ‘Khor chags, Nyar ma and Shel also constituted key religio-political centres of Historical Western Tibet, there is evidence for an ancient (and still ongoing) religious cult of this deity which included remarkable popular and public dimensions. These were (and in most cases still are) expressed on the occasion of festivals and rituals in the form of public appearances by trance-mediums and / or by way of material manifestations. Both phenomena are often accompanied by the performance of a type of religious dance by lay people or monks personating rDo rje chen mo. Other religious as well as secular dimensions of power can be seen in the (self)designation of this deity as owner (bdag po) of the monastery where she resides and in a corresponding system of socio economic organisation and of economic provision for maintaining the monastery on the part of the lay population.

Based on extensive field research in recent years in these places, in particular in ‘Khor chags (Purang County, Ngari Prefecture, Tibet Autonomous Region) and Tabo (Lahaul-Spiti District, Himachal Pradesh, India), selected examples of major festival and ritual traditions associated with this protective deity, such as the Nam mthong festival in ‘Khor chags and lCags mkhar festival in Tabo, will be discussed.

1 Vitali, Roberto (2003) “A chronology (bstan rtsis) of events in the history of mNga’ ris skor gsum (tenth-fifteenth centuries)”, in: A. McKay (ed.) The History of Tibet. Volume II. The Medieval Period: c.850–1895. The Development of Buddhist Paramountcy. London-New York: RoutledgeCurzon, p. 57.

Marialaura Di Mattia (Roma)

The religious factor as a political tool in the establishment of the Western Himalayan kingdoms.

The paper will focus on the modalities of the peaceful penetration in the Western Himalayan territories – in the core of the ancient Zhang.zhung kingdom – by the offspring of the Yar.lung royal family headed by sKyid.lde Nyi.ma.mgon.

One of the subjects which deserves further historical researches and investigations is that sovereignty all over the Western Himalayan areas probably developed , grew and expanded gradually through economical and political steps, like the support to international trade and the transformation of previous opponents into present allies.

Therefore, the history of the rising and strengthening of the mNga’.ris kingdoms could be based on a non-violent conquest.

In the cultural cross-road of mNga’.ris sKor.gsum at the beginning of the Second Diffusion of Buddhism, a few elements should be taken into consideration as, for instance, the institution of the ‘monk-king’ and the ‘uncle-nephew’ relationship in the Gu.ge royal family.

A case to study is the hypothesis of the transfiguration of ancient enemies into new guardians of the law, as expressed by artistic language: is this a process of co-opting and empowering local gods and divinities?

Perhaps the answer can be searched in the light of the discovery of the representation of a meaningful recurring series (often appearing as a couple) of Chos.skyong (dharmapala) beautifully painted or sculpted in several Lo.tsa’.ba lha.khang scattered in Spiti and Kinnaur.

Erberto Lo Bue (Bologna)

The main image in the Gtsug lag khang of Rgyal rtse and its religious, cultural and political meaning.

“I have shown elsewhere (“Considerations on the historical and political context of the iconography of three south-western Tibetan temples”, in Jean-Luc Achard, ed., Études tibétaines en l’honneur d’Anne Chayet, Droz, Genève 2010, pp.147-173) that the original name of the Chos rgyal lha khang in the Gtsug lag khang of Rgyal rtse derives from the statues of the three Tibetan emperors portrayed therein and that the statue of Avalokiteshvara was erected as their samaya. The predominance of Avalokiteshvara in the iconography of this temple coupled with the presence of his earthly manifestation, Srong brtsan sgam po, with the two other famous emperorsthat protected Buddhism in Tibet according to Tibetan tradition, implies that the dharmaraja of Rgyal rtse aspired to be, and presumably viewed himself as, a continuator of the religious activity of those three earlier dharmarajas, relating himself ideally to the earliest dynasty that had ruled over Tibet and whose first historical representative had chosen Avalokiteshvara as his tutelary deity. In other words the Chos ryal lha khang was conceived as a royal chapel endowed with religious as well as political meaning, before the temple’s original iconographic programme was altered by the introduction of a statue of Maitreya and its name accordingly changed into Byams pa lha khang.

In the present paper I extend my analysis to the Gtsang khang, the sancta sanctorum in the same Gtsug lag khang, as a result of my study of a few so far untranslated pages from the history of the kings of Rgyal rtse, and in particular to its main image, the gilded copper statue of Mahamuni whose central iron pillar was raised up by the dharmaraja in person. The list of contents in that big statue, ranging from a number of collections of texts in its bottom sections to relics of various kinds – bodily ashes, hair, nails, blood, bone accoutrements, rosaries, burdons, fragments of garments belonging to famous Indian and Tibetan Buddhist masters and translators, beside earth and water from the holiest Buddhist places in India – include relics of the Tibetan emperors (hair, garments and blood), which are placed in the section corresponding to the chest of the image, as well as relics of Sakyamuni himself, which had been the Tibetan emperors’ samayaand which are placed in the usnisa of the statue according to a criterion of growing importance from bottom to top, confirming the deep connection that the rulers of Rgyal rtse felt towards the glorious religious and lay past of the Tibetan empire. In that respect the relics filling the statue of Mahamuni summarize the deep and intimate religious, cultural and political meanings lying behind the construction and iconographic programmes of the whole monastery of Rgyal rtse”.

Laura Giuliano (Roma)

OēÅ¡o and the King

Some scholars have pointed out the role of OēÅ¡o in Kuá¹£āṇa kingship as emerging from the analysis of certain characteristics of his image on the coins. On Kaniá¹£ka and Huviá¹£ka specimens, for example, he is represented with extended lower right hand, holding a water-vessel turned downwards, a gesture alluding most probably to the legitimation and consecration of the sovereign through the royal abhiá¹£eka.

In this paper we shall try to go into the subject, studying in detail the relationship between OēÅ¡o and the King on the basis of the iconographical data and trying to reveal the possible meaning and values of some figurative elements of his image in the Kuá¹£āṇa coinage, with the help of textual references especially drawn from late Vedic literature.