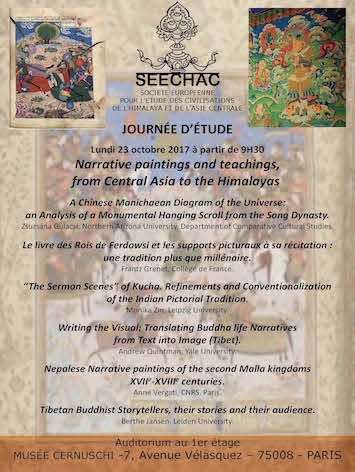

Narrative paintings and teachings from Central Asia to the Himalayas

(Peintures narratives et enseignements, de l’Asie centrale à l’Himalaya)

Le 23 Octobre 2017 dans l’Auditorium du Musée Cernuschi.

Cette « Journée d’études » constituait la cinquième rencontre internationale organisée par la SEECHAC depuis sa fondation, après celles de Rome, Paris, Vienne et Heidelberg. Elle a rassemblé un public fourni, et s’est assurée la participation d’éminents collègues venus de l’étranger. Les sujets abordés ont couvert l’ensemble du champ géographique et chronologique dans le domaine de compétence de la SEECHAC, de l’Iran à la Chine en passant par le Népal et le Tibet.

Titres des communications

A Chinese Manichaean Diagram of the Universe: An Analysis of a Monumental Hanging Scroll from the Song Dynasty.

Zsuzsana Gulacsi, Northern Arizona University, Department of Comparative Cultural Studies.

A large medieval Chinese silk painting belonging today to the Nara National Museum located in Nara, Japan, was identified in 2010 by Yutaka Yoshida as a depiction of the cosmos according to the Manichaean religion. Two other small silk fragments originally believed to stem from a separate work of art are here shown to be pieces of an unsuspected missing top section of the same painting. With the original hanging scroll digitally restored and assessed with the aid of a line-drawn diagram, it is now possible to offer a systematic analysis of its overall design and individual sub scenes that incorporate previous interpretations, correct others, and add several new insights. In light of early Manichaean cosmological texts paired with a formal artistic analysis, this presentation explores visual catechism as it is conveyed within a complex iconography of over 900 motifs distributed in a layered symmetry that merges anthropomorphic, geomorphic, and architectonic features into a monumental cosmic map of salvation.

Le livre des Rois de Ferdowsi et les supports picturaux à sa récitation ; une tradition plus que millénaire / The book of the Kings of Ferdowsi and the pictorial supports to his recitation; more than a millennium’s tradition.

Frantz Grenet, Collège de France.

La tradition des Shāhnāmekhān, récitateurs du Shāhnāme, le « Livre des Rois » de Ferdowsi (début 11e s.), l’épopée nationale de l’Iran, est restée vivante en Iran et en Afghanistan. En Iran les récitations qui attirent le public le plus nombreux se déroulent devant de grands tableaux peints. Elles s’accompagnent parfois de plages improvisées et de gesticulations (la « performatrice » la plus fameuse, Gordāfarid, est une vedette de la télévision iranienne, bien qu’émigrée à Los Angeles).

Plusieurs cycles peints dans des maisons particulière à Pendjikent (non loin de Samarkand), exécutés dans les années 740 mais alors que la ville n’était encore que peu islamisée, montrent des scènes épiques se déroulant en longs bandeaux peints sur trois murs de la salle de réception. Rostam, champion des rois, peut être identifié dans trois cycles, dont l’un correspond à un épisode connu du Shāhnāme. Il est très probable que des récitations se déroulaient devant ces peintures. La disposition des épisodes sur les murs fait soupçonner qu’elles sont dans certains cas la transposition de rouleaux historiés.

The tradition of the Shāhnāmekhān, reciters of the Shāhnāme, Ferdowsi’s « Book of Kings » (early 11th c.), Iran’s national epic, remained alive in Iran and Afghanistan. In Iran, recitations attracting the largest number of people take place in front of large paintings. They are sometimes accompanied by improvised moments and gesticulations (the most famous « performer », Gordāfarid, is a star of Iranian television, although emigrated to Los Angeles).

Several cycles painted in particular houses in Pendjikent (not far from Samarkand), executed in the 740s, but when the city was still little Islamized, show epic scenes taking place in long banners painted on three walls of the reception room. Rostam, champion of kings, can be identified in three cycles, one of which corresponds to a known episode of Shāhnāme. It is very probable that recitations took place before these paintings. The arrangement of the episodes on the walls makes one suspect that they are in some cases the transposition of illustrated scrolls.

“The Sermon Scenes” of Kucha. Refinements and Conventionalization of the Indian Pictorial Tradition.

Monika Zin, Leipzig University.

Narrative paintings must have played an enormous role for the dwellers and the visitors of the Buddhist caves in Kucha since they cover most parts of the walls and barrel vaults. The stories themselves, as well as the tradition to illustrate them in the monasteries, was adopted from India together with a set of highly sophisticated techniques of narrative representation. However, in Kucha these techniques were further developed to achieve a condensation of narrative representations; the aim was to show as many topics as possible within the space available. This resulted in a « telegraphic style » of pictorial story-telling; one picture can contain events taking place in different re-births, while in other cases an entire tale is represented just by one single attribute and alongside an image of the preaching Buddha we may find not only the depictions of his audience but also of the content of his sermon.

Writing the Visual: Translating Buddha life Narratives from Text into Image (Tibet).

Andrew Quintman, Yale University.

Accounts of the Buddha’s final life are ubiquitous across Tibet. Among the most extensive and striking are those in the corpus of literary and visual materials produced by the seventeenth-century luminary Tāranātha Kunga Nyingpo (1575–1634) at his monastic seat of Phuntsokling in the Tibetan region of Tsang. This paper examines Tāranātha’s work entitled A Painting Manual for the Hundred Acts of the Teacher, Lord of Śākyas (Ston pa shākya dbang po’i mdzad brgya pa’i bris yig). This text exemplifies the little-studied genre of Tibetan writing known as the painting manual (bris yig). In it, Tāranātha self-consciously bridges two sets of Buddha vitae: his literary narrative in 125 chapters called The Sun of Faith (Dad pa’i nyin byed) and the narrative murals executed in his monastery’s second floor gallery, covering some 150 square meters, referred to as “the Boundless Design” (bkod pa mtha’ yas). The Painting Manual covers the entire arc of the Buddha’s life story as told in The Sun of Faith, and contains scene-by-scene instructions for its visual representation. Tāranātha’s Painting Manual thus inhabits in a middle ground between two media, effectively translating text into image. This paper draws on Tāranātha’s writings and a complete site documentation of his murals to reflect upon the different kinds of stories textual and visual narratives tell, and how the translation from one to the other leads to new forms of storied knowledge.

Nepalese Narrative paintings of the second Malla kingdoms XVII-XVIII.

Anne Vergati, CNRS, Paris.

In the three Malla kingdoms Patan, Kathmandu and Bhaktapur of Kathmandu Valley a new category of paintings appeared at the end of XVIth century. These are long scrolls (Newari vilampu) depicting the legends of foundation of monasteries, Buddhist legends, a festival (yatra) or a pilgrimage. These scrolls were exhibited in the courtyard of the monasteries during the holy month of Buddhists, the month of August. In the past, they have been used for teaching the Buddhist legends, for instance the legend of prince Visvantara, the creation of the valley by the bodhisattva Manjusri or the history of a monastery.

They show a strong Indian influence for the costumes and landscape but at the same time they have create a specific Nepalese style. Often, they represent monuments such monasteries, temple, stupa which are characteristic for Malla kingdoms. These paintings are important documents for the cultural history of the Malla kingdoms.

Tibetan Buddhist Storytellers, their stories and their audience

Berthe Jansen, Leiden University.

In this paper, I discuss the tradition of Buddhist storytelling in Tibet and the Himalayas. The Lama Manipa (or bu chen) were men and women who travelled far and wide to tell their stories to ordinary people. Significantly, they used traditional paintings (thang kha) to illustrate their narratives. The often colourful and emotive stories revolve around persons important in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition and are presented to the public as portraying religious history. Currently, there appears to be only one active storyteller left. Using the interviews I conducted with this last Lama Manipa, the narrative thang khas, and textual references to this tradition as my sources, I consider the stories told, and shown, to an audience of believers. I argue that, ultimately, an investigation into this (semi-) ‘folk’ religious tradition offers us a glimpse into the once lived religious experiences of ordinary Tibetan Buddhists.