Conference by Berthe Jansen (University of Leyden), at 5.30 PM at Maison de l’Asie, 22 avenue du président Wilson, 75016 PARIS.

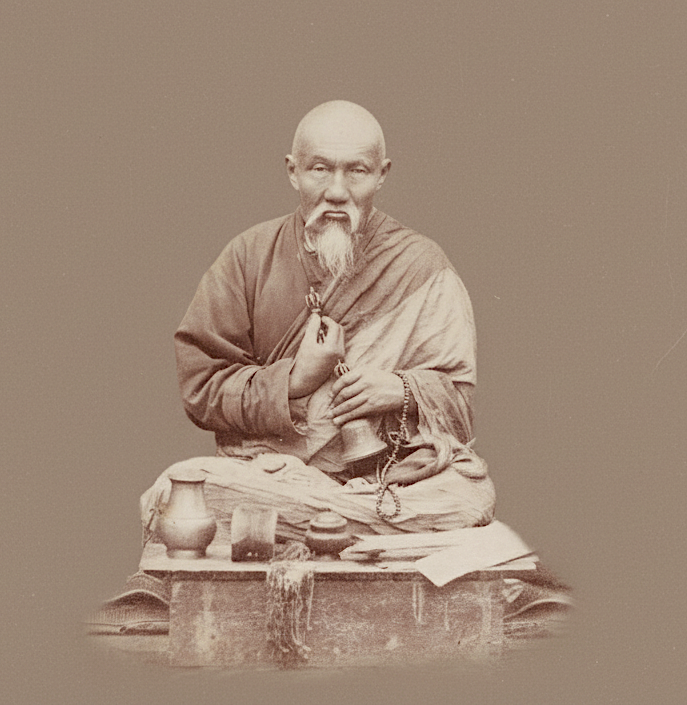

On July 11, 1892, a grand procession wound through the narrow streets of Darjeeling. A large crowd gathered to receive the blessings from Buddhist relics that had arrived from Sri Lanka. The attendees included Anagārika Dharmapāla (1864-1933), members of Sikkim’s royal family, Western Theosophists, abbots of local monasteries, and the Bengali scholar Sarat Chandra Das. Sherab Gyatso (shes rab rgya mtsho), a Mongolian monk, founder and abbot of Yiga Chöling (yid dga’ chos gling) monastery—commonly known as Ghoom monastery, carried the casket containing the relics. The procession concluded at the residence of the Raja of Sikkim, where Sinhalese and Tibetan Buddhists delivered speeches. The then 71-year-old Sherab Gyatso, speaking Tibetan, talked of the history of Buddhism and how it spread from India to Tibet and Sri Lanka.

Scholars of the Tibetan language recognise this Mongolian monk for his crucial role in producing one of the field’s most enduring dictionaries, edited by Sarat Chandra Das (1902). Historians studying Tibet’s relationship with the British Raj may know him as a British informant and Tibetan language instructor for agents operating in Tibetan territories. Yet the pan-Buddhist procession in which Sherab Gyatso played such an important role —witnessed and documented by Henrietta Müller, a prominent Theosophist and women’s rights advocate—shows him in a different light, namely as a monk involved in building bridges between Buddhist communities and spreading the Dharma. While working on my ERC-funded project “Locating Literature, Lived Religion, and Lives in the Himalayas: The Van Manen Collection,” I uncovered a short autobiography by this multifaceted figure in the Leiden archives. This text represents the only known surviving piece of writing by Sherab Gyatso in Tibetan. In this talk, I discuss the autobiography’s contents in the light of the lama’s relationships with fellow Buddhists, missionaries, British officials, and Darjeeling’s diverse population. More significantly, I position the Gelug monastery he purportedly established in 1875 as a cultural contact zone where people from various religious and ethnic backgrounds studied Tibetan language and Buddhism. I contend that Ghoom monastery functioned as the first truly international Tibetan Buddhist institution, making its history and contribution to Tibetan and Buddhist studies worthy of more scholarly and public attention.